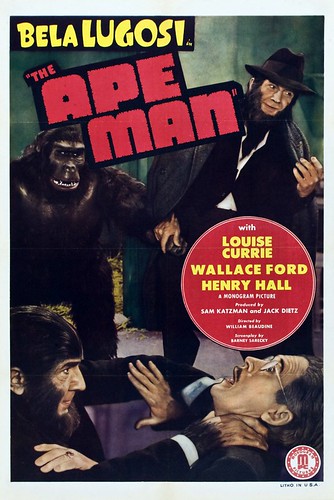

Director: William Beaudine

Cast: Bela Lugosi, Louise Currie, Wallace Ford, Henry Hall

Caveman Quotient: Either 0% or 100%, depending upon your point of view

Analysis:

As I write this, I am looking out the window of my room in a flophouse by the East River. I can hear sirens in the distance, growing closer, and as the cars screech to a halt outside I type on, mad and uncaring, desperate to finish the last line of the review before the police burst in and tear me kicking and screaming from my Remington. But I deserve it all, you know. You see, I have broken my own rules. The Ape Man isn’t a caveman movie at all.

It’s a question of genetics, really. While there’s nothing all that controversial about a caveman movie in which a person regresses to a proto-human state – Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde did it, Altered States did it, and I’m pretty sure I can argue that Howling II: Your Sister is A Werewolf did it on a technicality, even if it does posit that Homo sapiens is descended from canines. The Ape Man, however, is not a tale of regression, but of transformation. Simply put, Bela Lugosi turns himself into an ape by injecting himself with the spinal fluid of a silverback gorilla. That’s not a caveman movie – that’s just weird.

The Ape Man is a product of the notorious Poverty Row studio Monogram Pictures, Corp., and despite its seemingly exceptional insanity, it’s hardly atypical of their output. Monogram are infamous for having combining a total lack of resources with a complete disregard for quality, compensating with a heavy dose of crazy and former star/future Ed Wood, Jr. collaborator Bela Lugosi embarrassing himself in a series of increasingly ludicrous roles. You sort of have to feel sorry for Bela Lugosi. He started-out on top, changing the face of cinematic horror with his ground-breaking (albeit, not very good) role in Dracula, went on to star in a number of genuinely good films, including the stone-cold classic White Zombie, and then set out on a long, slow decline that would see him closing-out his career as a broken-down morphine addict forced to lose a wrestling match against an inanimate rubber octopus. Even if he was partially to blame, going about doing silly things like turning down the role of Frankenstein's monster because it didn't have any lines, you can really sympathise with him a bit in this film when, after just having engaged in a battle of wits with his ape, he collapses into a chair and declares "I have messed everything up!". On the other hand, his loss was our gain, since while I certainly wouldn’t wish any ill on the man, I certainly do enjoy watching him make a fool of himself.

And boy! What a fool he does make. Indignity, thy name is The Ape Man. Equal parts unfunny comedy and non-horrific horror film, the only things this film has going for it are Lugosi’s performance and a healthy dose of silliness. Lugosi is Dr. James Brewster, a “world-famous gland expert” with an unexplained Hungarian accent, who has suddenly up and vanished, out of the blue. The newspapers are going wild about it, but no-one can find a trace of him, and many people are starting to suspect that poor old Dr. Brewster may be dead.

Enter Brewster’s sister, Agatha (Minerva Urecal). She’s just returned from a ghost-hunting trip in Europe, and is deeply shocked to learn of her brother’s disappearance. She goes to talk to Dr. George Caldwell (Henry Hall), Brewster’s long-time friend and colleague, hoping to get some sort of perspective on events. Caldwell, for his part, is quick to reassure Agatha that her brother is alive and safe. It turns-out that one of his experiments went awry, leaving him changed somehow, and rather than deal with the public outcry that would accompany revealing himself, Brewster has instead holed-up in the secret laboratory hidden beneath his house, where he is busily working on a cure. Only Agatha should brace herself. Her brother's appearance has undergone some rather drastic changes.

There’s really no way to explain in words the glorious nature of the scene in which Lugosi first appears. Agatha and Caldwell wind their way down along the staircase concealed behind Brewster’s living room fireplace. They cross the laboratory, and Caldwell trips a lever that exposes a hidden cage. In the cage, there squats a silverback gorilla, here portrayed via unconvincing man-in-suit. Beside the ape, all snuggled-up, is a figure in black. It stirs. It rises. Agatha looks on in shock -- and the thing turns towards her -- and it looks up at her -- and Caldwell brandishes his pistol as the thing falls against the cage. And what is this thing, you ask? What, this grotesquery? It looks like a man, yet it walks like an ape, and its pale and trembling fingers are cloaked in fur. And then it speaks. By God, it speaks! It is Bela Lugosi – and he hasn’t shaved in days!

Bela Lugosi, transformed into a man-ape and shacking-up with a gorilla. Really, could you concoct a more lurid scenario?

This, then, is the extent of Dr. Brewster’s transformation: he slouches somewhat, he swings his arms a little, and he has facial hair that bears an equal resemblance to the beard of a Mennonite and the helmet of Juggernaut. Looking at all this, there is really no reason why he couldn’t just apply some Nair and go topside. But then I suppose there’d be no film. I mean, I guess they could have made Lugosi wear the gorilla suit, but then they would have lost the face recognition of their “star”. On the other hand, they would have gained an intelligent mad scientist gorilla who spoke with a Hungarian accent, and that is worth more than all the Bela Lugosi in the world.

As I may have alluded to once or twice in the introduction, Brewster found himself in this state after injecting himself with the spinal fluid of a gorilla. Why I do not know. I suppose he and Caldwell were trying to test the viability of gorillas as spinal fluid donors, which would have taken about twenty seconds of dialogue to establish but which is instead glossed over in favour of scenes of Bela Lugosi engaging in chest-beating displays of alpha-male superiority with his pal the preternaturally intelligent test-ape. So I suppose the film-makers made the right call on that one. Anyway, Brewster is naturally upset about the unexpected side-effects of his course of ape-juice, and is eager to return himself to the ranks of humanity. He figures (perhaps reasonably) that since injecting himself with simian spinal fluid transformed him into an ape, injecting himself with human spinal fluid will transform him back into a man. Like I said, fairly reasonable.

Less reasonable is Brewster’s determination to go through with this plan. You see, for the spinal fluid to take effect, it has to be fresh – which means that any donors for the fluid have to still be living when the stuff is removed. And needless to say, the removal of a significant quantity of spinal fluid from a living human is hardly about to do wonders for their health. If Brewster wants his humanity back, then he’s going to have to kill for it.

Of course, from here you can pretty much write the film itself. Caldwell refuses to help Brewster with his scheme. Agatha sides with Brewster out of misplaced affection, and the brother and sister strong-arm Caldwell into helping them, having Caldwell inject Brewster with the spinal fluid of Caldwell’s butler. The first treatment doesn’t work, so Brewster ups the ante and starts staging murderous night raids to amass more fluids, sicking his pet gorilla on helpless citizens and then draining them with a syringe. In the end, it all goes pear-shaped when Caldwell throws self-preservation to the wind and takes a stand against his crazed partner, meeting his end but striking a blow for common decency in the process. In the final moments of the film Brewster is cornered in his laboratory, and murdered by his gorilla in the course of a fight over an attractive girl. Moments later, the police arrive, rescue the girl and shoot the gorilla, putting an end to the nasty business once and for all.

Really, there is the germ of a good idea in there somewhere. Granted, it’s probably a good idea that was stolen from an earlier film that I’ve never heard of, and I know it would crop-up again in a bunch of films that I can’t remember, but being derivative doesn’t necessarily preclude being good. The idea of a scientist accidentally mutating himself into a vampire is a simple but effective one, giving an element of ethical and psychological complexity (not to mention a nice Elizabeth Bathory-style twist) to the hoary old R.L. Stevenson-inspired “Man turns himself into a monster” premise. Probably the film that it reminds me of the most in this regard is The Little Shop of Horrors, where a loser feeds people to a carnivorous plant out of a belief that his popularity hinges on the plant’s survival. Except, you know, The Little Shop of Horrors actually did something with the idea. And, despite being just as cheap and rushed as The Ape Man, it didn’t suck.

Putting aside my obsession with selfishly-motivated vampirism as a plot point in horror stories, I suppose I should say something about the rest of the film. It doesn’t really bear thinking about, to be honest. Did you know that, in describing the film, I completely avoided mentioning the two reporter characters which take-up half the running time snooping, trying to dig-up dirt on Brewster? There’s reporter Jeff Carter, who’s a wise guy, and the female photographer, who’s named “Billie Mason”- and who as a consequence keeps getting mistaken for a man. They do the fairly typical low-rent Grant/Russell hard-boiled banter shtick, largely fail in their goal of providing a source of legitimate comedy, and wind-up almost entirely superfluous to the plot. Mostly they just keep showing-up at Brewster’s house, padding-out the running time by bothering Agatha with questions about her missing brother. It’s only in the last few minutes of the film that they do anything of significance, and really this just consists of Billie wandering into Brewster’s house while everyone’s out, getting nabbed by the Mad Doctor after he returns home from visiting with Caldwell, and serving as the requisite beauty for Carter to rescue at the end, thus proving to both himself and the audience that, strong-headed and capable or no, a woman is still a woman and she will always need a man – if only to serve as protection against murderous apes.

At the same time as I loathe the superfluousness of this sub-plot, I must admit that the two actors playing Billie and Jeff are reasonably likeable. I mean, Wallace Ford keeps flubbing his lines, and his character is a chauvinist jerk, but in the end he at least has a trustworthy face. Louise Currie, on the other hand, despite having almost nothing to work with, gives something close to an actual performance, and with a director who gave a damn she might even have been good. I mean, yes the dialogue is leaden and the pair’s sense of comic timing is severely impaired, but you take what you can get in these sorts of films. At least they don't read their lines off of the back off props like the guy who plays their editor. The duo’s presence also facilitates one of the film’s most interesting moments, a completely ludicrous climactic plot-twist involving a man who has been popping-up throughout the film and prompting characters on how they should respond to certain situations. It’s not at all a good twist, and the set-up is long and painful, but it really is something to see in action.

In the end, there’s not much one can say about The Ape Man. Well, not much that’s all that constructive, anyway. With a good script, better actors, a budget and a competent director, it might have been quite good, in a screwball sort of way. But then, that goes for pretty much every crappy movie. As it stands, The Ape Man is really only worth it for the outlandishness of its premise, and the schadenfreude that arises from watching Bela Lugosi done-up with false mutton-chops, palling around with a gorilla and ooking and ahhing like a monkey. But on the other hand, that’s already more than anyone could ever reasonably ask.

Looking over the above paragraphs, it is self-evident that The Ape Man is not a caveman film. A gorilla never is, was or will be a primitive human, and so transforming oneself into one of our simian brethren can hardly be considered the same as regressing into a Neanderthal state. At the same time, however, it should be clear why I decided to cover such a fundamentally ridiculous film. And so I hope that anyone reading this will forgive me, for – much like Bela Lugosi agreeing to star in this crummy, crummy film – I have forfeited what's left of my honour for the greater good.

Or something like that.

Rating:

Special Consideration – The One-Horned Armadillo of Unconventional Appeal